AR: https://kedencentre.org/2025/11/23/sudan-on-the-edge-of-language/

Executive Summary

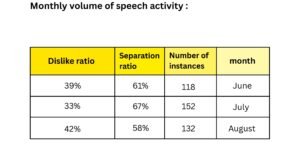

- General Background Since the outbreak of war in Sudan in 2023, the country has witnessed an unprecedented wave of social and political division, clearly reflected in the digital space through the escalation of hate speech and separatist discourse. Within the framework of its “Safe Voice” program, Kaden Center conducted a qualitative and quantitative analysis of 400 digital posts and comments on the platforms (Facebook, X, TikTok) during June, July, and August 2025, with the aim of understanding the relationship between hate speech and separatist discourse and monitoring the linguistic and social transformations that express the fragmentation of national identity.

- Monitoring and Analysis Methodology The report relied on two complementary methodologies:

- Qualitative analysis: Studying linguistic, semantic, and symbolic features in digital texts and classifying them into categories: dehumanization – incitement – threat – false legitimization.

- Quantitative analysis: Extracting digital indicators from three monthly data tables covering monitored posts during the study period and analyzing patterns, frequencies, and correlations. Data was processed using digital analysis tools and NVivo software to identify discourse trends and their geographical and thematic distribution.

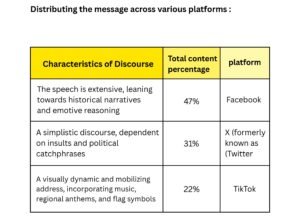

- Key Findings A. Rise of Separatist Discourse Posts calling for separation increased by more than 35% between June and August 2025. Most active platforms: Facebook (48%), X (34%), TikTok (18%).

B. Close Link between Separatism and Hate More than 70% of separatist posts contained elements of dehumanization or direct incitement. In 45% of cases, verbal incitement and threats of violence accompanied calls for separation.

C. Patterns of Separatist Currents Three main currents were identified:

- “River and Sea” current – Advocates preventive separation based on “geographical and cultural purity.”

- “Greater Darfur” current – Presents separation as liberation from historical injustice.

- “Center” current – Frames separation as a withdrawal resulting from chaos and the state’s abandonment of central communities after the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) took control of central Sudan.

D. Intensity and Qualitative Transformation of Discourse

- Average discourse intensity rose from 3/5 to 4/5 during the study period.

- The shift from analytical to mobilizing and inciting language is an indicator of the normalization of hate as a means of political expression.

- General Implications

- Separatist discourse has become a tool for reproducing regional hatred rather than a rights-based political project.

- The concept of the right to self-determination is being used incitingly to justify isolation and discrimination.

- The disintegration of national identity in the digital space reflects the collapse of trust between Sudanese components and the absence of a unifying national voice.

- The continuation of this discourse without intervention will lead to the institutionalization of digital hatred and its transformation into a fixed intellectual and social structure that will be difficult to dismantle in the future.

- Recommendations A. Public Policy Level

- Launch a national charter to combat hate speech and separatism, drafted with participation from state institutions and civil society.

- Include digital hate issues in transitional justice processes as symbolic crimes that contributed to dismantling the social fabric.

- Reform media and digital laws to ensure freedom of expression without allowing incitement to discrimination or violence.

B. Digital Media and Civil Society Level

- Establish a permanent digital observatory to monitor and track the evolution of hate speech and separatism online.

- Promote citizenship and cultural diversity discourse through counter-campaigns (#Safe_Voice, #Sudan_Unites_Us).

- Cooperate with international platforms (Meta, X, TikTok) to activate reporting and removal policies for inciting content.

C. Research and Documentation Level

- Create a national database for hate speech and separatism to enable researchers to analyze trends over time.

- Support comparative studies between Sudan and countries that experienced similar divisions.

- Expand training programs for researchers and media professionals on digital discourse analysis tools.

This report confirms that Sudan is living through the most dangerous phase of symbolic disintegration, where war is no longer fought only with weapons but with language, words, and symbols. Addressing hate and separatist discourse requires a comprehensive strategy that combines legal deterrence, community education, and political reform. For the language that divides can also rebuild — once it is redefined as a tool for justice, dignity, and shared living.

Introduction and General Context

- Report Background This report is part of the “Safe Voice” program implemented by Kaden Center for Justice and Human Rights as part of its efforts to promote safe discourse culture and combat hatred in the Sudanese digital space. The ongoing war in Sudan since 2023 has imposed a new reality of societal disintegration and political division, turning digital platforms into open arenas for mobilization, incitement, and reproduction of regional and ethnic narratives.

In this context, separatist discourse has emerged as one of the most dangerous manifestations of the crisis. Calls for separation are no longer presented as a political option based on the principle of self-determination but as a direct extension of hate speech, marginalization, and mutual discrimination among Sudanese components. Hence, this report monitors and analyzes this phenomenon as a linguistic and social indicator of the depth of fractures threatening Sudan’s future and symbolic unity.

- Importance of the Report This report is the first of its kind to integrate qualitative and quantitative analysis of hate and separatist patterns in Sudanese digital content, based on a broad sample of 400 documented posts and comments on Facebook, X (Twitter), and TikTok collected during June–August 2025. Its importance lies in:

- Providing a systematic scientific analysis of hate and separatist language, away from political impressions.

- Linking digital discourse phenomena to structural transformations in Sudanese society.

- Offering a qualitative database that can later be used in transitional justice programs or human-rights monitoring.

- Problem Statement The central question of the report is:

- How do hate speech and separatist discourse interact in the Sudanese digital space?

- Does separatist discourse represent a legitimate exercise of the right to self-determination, or is it a tool to justify discrimination and symbolic violence? The importance of this question stems from the conceptual overlap between freedom and justice in the current Sudanese context, where separation is presented as a symbol of victimhood while simultaneously being reproduced as a language of exclusion.

- Report Objectives The report aims to:

- Monitor and analyze patterns of separatist discourse on Sudanese digital platforms.

- Understand the relationship between separatism and hate speech at its various levels (incitement, dehumanization, threat, legitimization).

- Identify the main actors and currents producing separatist discourse.

- Provide practical and human-rights-based recommendations to support a unifying national discourse that counters hatred.

- Report Hypotheses

- Separatist discourse cannot be separated from the structure of hate speech.

- Its rise reflects the national crisis more than it represents an organized political project.

- User interaction with this discourse reflects a decline in trust between regional and ethnic components.

- Social media platforms have become a medium for rebuilding fractured identities in the absence of unifying national institutions.

Conceptual Framework

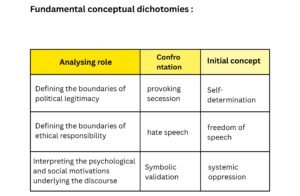

Defining core concepts is essential to understanding the phenomenon of separatist discourse in Sudan, especially given the ambiguous and multiple uses of concepts such as “self-determination,” “separation,” and “political freedom,” which are used in public discourse sometimes in their legal sense and sometimes as tools for incitement or regional mobilization. This framework aims to clarify the boundaries between the legitimate right to self-determination and discourse that instrumentalizes this right to justify hatred and division.

- The Concept of the Right to Self-Determination The right to self-determination is a fundamental collective right enshrined in international law, granting peoples the freedom to choose their political and social system. It is affirmed in several international instruments, most notably:

- Article 1 of the 1966 International Covenants (Civil and Political Rights; Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), which states: “All peoples have the right to self-determination.”

- Article 55 of the United Nations Charter, which links self-determination to respect for equality of rights. However, this right is not exercised in a vacuum but within the principles of state unity, rule of law, and non-discrimination. In the Sudanese context, it is necessary to distinguish between:

- Self-determination as a legitimate political right exercised through peaceful and democratic means.

- Inciting separatism, which uses exclusionary or hateful language to justify division on ethnic or regional grounds.

- The Concept of Hate Speech Hate speech is defined in international law literature as any form of verbal, symbolic, or digital expression that incites discrimination, violence, or hostility against a group based on its ethnic, religious, regional, or other identity. Article 20(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights mandates the prohibition of “any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence.” The report distinguishes three main levels of hate speech:

- Direct incitement: Explicit calls for violence, separation, or revenge.

- Dehumanization: Describing the other with animalistic, demonic, or inferior attributes.

- Symbolic legitimization: Justifying discrimination or isolation on the basis of one group’s superiority over another.

- Overlap between Self-Determination and Hate Speech Field data analysis shows that a large portion of separatist discourse in Sudan borrows the vocabulary of international rights to justify positions that involve contempt or dehumanization of other groups. Phrases such as “It is our right to decide our fate away from them” or “We don’t want to mix with northern people” blend demands for political independence with incitement to social isolation, making “self-determination” here a language of hatred rather than a demand for freedom. This pattern is one of the most dangerous forms of discourse because it clothes hatred in the garb of justice and presents separation as a moral salvation rather than a political project. Thus, separatist discourse in the Sudanese context feeds on narratives of collective victimhood while simultaneously reproducing that same victimhood against the different other.

- Boundaries of Freedom and Prohibited Speech Prohibiting hate speech does not mean restricting freedom of expression but rather framing it ethically and legally to ensure it does not become a tool for symbolic violence. Freedom of opinion is guaranteed under Article 19 of the ICCPR, but it is restricted when it conflicts with others’ rights to dignity and security. In this context, the report indicates that the dividing line between legitimate expression and harmful speech lies in:

- The speaker’s intent (is the aim expression or incitement?).

- The context in which the speech is published (discussion or mobilization?).

- The expected impact (does it lead to actual harm or discrimination?).

- Analytical Framework of the Study The report relied on constructing an analytical framework based on three main conceptual dyads: [Table 1 – omitted in text but referenced] This framework is used later to interpret qualitative and quantitative results, serving as the theoretical foundation linking language, identity, and politics in the Sudanese case.

General Context and Dynamics of Interaction between Hate Speech and Separatist Discourse

Understanding the rise of separatist discourse in Sudan cannot be detached from the broader political and social context that produced the war and reshaped the public sphere. Since the collapse of the political process in 2023, Sudan has been experiencing comprehensive institutional disintegration accompanied by symbolic disintegration of national identity and a collapse of trust between regional and ethnic components. In this fragile climate, language has become a tool for entrenchment and survival, and digital discourse has become a mirror of power and belonging struggles rather than a means of communication and understanding.

- Political and Social Context of the War The war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces has fragmented the national space into islands of military control, each with its own language, discourse, and narrative. In western regions, narratives have been rebuilt around historical victimhood and lost justice. In the north and east, discourse has centered on “survival from chaos” and “protecting Nile Valley identity.” In the center, a feeling of betrayal and symbolic withdrawal from the idea of the nation has prevailed. This reality has created fertile ground for reproducing divisive discourse as a psychological response to the absence of the state and hate speech as a means of expressing collective pain rather than just a political stance.

- Digital Media as a New Political Actor Since 2023, social media platforms in Sudan have become the actual alternative to traditional political and media platforms. They have formed an unregulated public space where expression mixes with incitement and victimhood with counter-incitement. Influential pages and closed groups have turned into centers for producing competing narratives that vie to define “who is the real Sudanese?” and “who deserves to remain?” The report data shows that 83% of separatist posts and 70% of hate posts are produced by anonymous or explicitly regional-symbol accounts, indicating the transformation of the digital space into an area of unorganized mobilization.

- Dynamics of Interaction between the Two Discourses A. From Hate to Separation In many cases, discourse begins at an emotional level of blame or regional anger and gradually develops into an explicit call for separation. Hate here acts as a motivational mechanism for division, granting separation moral legitimacy based on exclusion (“We are better than living with them”).

B. From Separation to Hate Conversely, separatist discourse itself generates waves of counter-hate from the other side, creating a closed linguistic cycle of mutual hostility. Every call for separation produces counter-discourse describing separatists as “traitors,” “slaves,” or “opportunists,” reigniting symbolic violence and deepening the fracture in collective consciousness.

C. Mutual Interaction across Platforms Analyses show that digital platforms function as reciprocal theaters where hate speech and separatist discourse feed off each other through “emotional circulation.” Every inciting post on Facebook is met with a counter-attack on X, while TikTok becomes a tool for glorifying regional symbols and building “linguistic heroes” from divisive content creators.

- Factors Feeding Both Discourses

- Political and institutional vacuum: The absence of unifying national leadership has made separatist discourse the sole speaker on behalf of victimhood.

- Media polarization: Platform algorithms feeding controversial content have made hate more widespread than calls for unity.

- Collective trauma: Experiences of war and displacement have turned pain into a language of anger and hostility.

- Unresolved history: Lack of justice for past crimes (Darfur, Blue Nile, Nuba Mountains) has made separatist discourse appear a “natural” extension of historical victimhood.

- Symbolic mobilization: Using local symbols (crossed-out maps, regional colors, traditional songs) has made the discourse more impactful and emotionally legitimate.

Impact of the Discourse on National Identity

Separatist discourse has shifted from a discussion about “political borders” to a discussion about “moral identity.” The question is no longer “Who rules?” but “Who belongs?” This dangerous shift has caused Sudanese identity to be negatively redefined: “We are who they are not.” The interaction between hate and separatism does not produce a new geographical reality but a fragmented linguistic reality in which national symbols are splintered into regional slogans, and Sudan turns into contested linguistic maps inside the digital space.

Summary of the Section

- Separatist discourse is a linguistic output of the war, not an organized political project.

- It feeds more on emotional and symbolic discrimination than on objective interests.

- Hate speech and separatist discourse function as a closed loop of mutual stimulation, where each side justifies the other’s existence.

- The continuation of this dynamic threatens to turn hatred into an alternative national identity and separation into a natural everyday language in public consciousness.

Contemporary Separatist Currents and Their Linguistic Patterns

Analysis of Sudanese digital discourse during the extended war period (2023–2025) reveals the formation of three main separatist currents that differ in their ideological foundations and rhetorical vocabulary but share a common linguistic core based on redefining national identity through negation of the other. These currents are not limited to political or military elites but extend to local communities, popular pages, and digital influencers who reproduce these narratives through daily videos and posts.

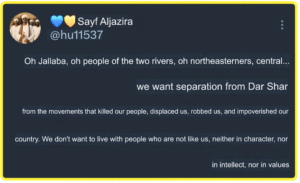

First Current: “Greater Darfur” – Separation as Salvation from Injustice This current emerges from the womb of the Darfur war and a long history of marginalization and impunity. It presents “Greater Darfur” as an independent political entity imagined as a space of “lost justice” and “restored dignity.” Its discourse includes:

- Collective victimhood language: repeated terms such as “we were robbed,” “they violated our land,” “we don’t want to return to them.”

- Religious and historical symbolism: concepts like “land of martyrs,” “home of the revolution,” “African heritage.”

- Reversed dehumanization: portraying northern inhabitants as “invaders” or “strangers.”

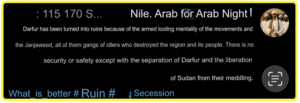

- Political legitimization: expressions such as “our right to self-determination,” “separation is justice, not hatred” to beautify hostile discourse. This current is strongly present on Facebook and TikTok, using hashtags such as #Darfur_Decides_Its_Fate, #Separation_Is_Justice, #Darfur_Not_Subordinate. It translates liberation from injustice into linguistic separation, turning justice discourse into exclusion discourse. It reflects a defensive psychological tendency more than a founded political project.

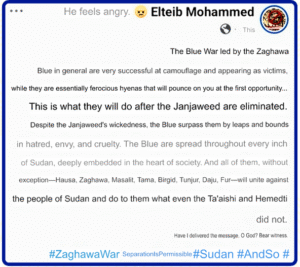

Second Current: “River and Sea” – Preventive Separation and Nile-Centric Discourse This current appears from pages and influencers belonging to the Nile Valley region and promotes the idea that “separation is better than drowning in chaos.” It stems from fears of “demographic and cultural threat” and presents separation as a means to protect “historical purity and original identity.” Its discourse is built on:

- Language of fear and warning: “We want to preserve our country before it is lost,” “separation is our salvation.”

- Symbolic self-elevation: words such as “purity,” “origin,” “Nile Valley identity.”

- Dehumanization of the other: referring to western groups as “invaders” or “militias.”

- Moral paradox: combining calls for internal peace with rejection of the different other. The discourse spreads on X (Twitter) and Facebook via hashtags: #River_and_Sea, #Separation_of_Dignity, #We_Protect_Our_Identity. This current uses separation as a symbolic shield rather than a political plan and reflects the fear of urban middle classes.

Third Current: “Center” Current In the central Sudanese region, particularly after the army’s withdrawal from Gezira and surrounding states, a growing separatist discourse has formed that reflects a deep sense of betrayal and exposure more than an organized political ambition. The security and institutional vacuum generated a feeling that the state, long centered in the north, had abandoned the center and left its people facing chaos without protection. This has unleashed voices calling for separation from the north and the establishment of an independent “Center” entity seen as a means of survival and regaining control over destiny. Recurring phrases include “We don’t want to remain subordinate to northern people” and “Leave us alone after you abandoned us,” revealing a tendency toward withdrawal from chaos rather than confrontation and a desire for shelter before seeking power. This current employs local symbols such as the Nile, the Gezira Scheme, and agriculture to build a new identity for the center presented as a realistic alternative to a collapsing nation. It can be described as “preventive separation,” where separation arises not from hatred or superiority but as an instinct for survival amid the loss of the state and collapse of trust in the center. Thus, the center — historically a symbol of national balance and meeting point between north and south — is turning into a space seeking self-salvation from a nation no longer able to protect it, signifying that division is no longer a marginal phenomenon from the peripheries but now extends to the very heart of Sudan.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The digital texts analyzed between June and August 2025 reflect the scale of transformation in political and social language in Sudan. Digital platforms are no longer mere spaces for expression but have become theaters for the disintegration of national discourse and the rise of divisive language as a tool of psychological and social resistance. Qualitative analysis reveals a network of vocabulary and symbols that reproduce hate and separation through three main linguistic mechanisms: collective salvation, dehumanization, and symbolic legitimization.

Separation as Collective Salvation Separatist discourse appears in many texts as a dream of salvation from chaos and war. Users speak of separation not as a political option but as a moral and existential salvation. Examples: “We don’t want to return to the old Sudan; Darfur is a state of justice, not slavery.” “It is our right to live away from northern people; we don’t want to be part of their failure.” These expressions reflect a deep sense of collective betrayal and a linguistic shift from expressing victimhood to embracing separation as a psychological remedy for trauma.

Dehumanization as a Linguistic Mechanism of Discrimination In numerous texts, dehumanization appears as a step preceding calls for separation. Other groups are described with attributes that diminish their dignity or exclude them from humanity: “These people have no good in them, no blood or humanity; our country will be cleansed after them.” “We won’t build a country with people who don’t resemble us.” This language places the other in a position of moral impurity and makes separation appear as a purifying act.

Incitement and Symbolic Violence Texts contain inciting phrases calling for confrontation or “cleansing,” employing images of heroism and symbolic victory: “Separation is our final battle against the invaders.” “There is no coexistence after what happened; Darfur must be fully liberated.” “Every time we try unity, they kill us; separation is the solution.” This discourse wears the cloak of resistance but essentially legitimizes symbolic violence.

Symbolic Legitimization and Sacred Separation Many texts include religious and historical references used to sanctify the idea of separation: “Separation is divine justice, and whoever opposes us opposes God’s will.” “We are the origin, and they are followers; returning to the origin is a virtue.” Here, separatist discourse becomes a closed linguistic faith, discussed not as a political option but as an absolute truth that cannot be opposed.

Supporting Symbols in the Discourse Widespread linguistic and visual symbols reinforce the separatist meaning:

- Purification symbolism: “cleanse,” “wash,” “purify our country.”

- Land symbolism: “our pure land,” “our home does not accept strangers.”

- Purity symbolism: “preserve our blood,” “return to the origin.”

Conclusion of Qualitative Analysis

- Separatist language in Sudanese digital discourse is emotionally charged more than logical.

- Separation is presented as a psychological solution to historical victimhood, not a political plan.

- Dehumanization is used to justify division under the guise of “justice” or “purity.”

- Religious and historical legitimization gives the discourse a mobilizing dimension.

- The most dangerous aspect is that this language normalizes division and makes hatred part of identity.

Quantitative Data Analysis

2. Overall Volume of Discourse Activity During the full monitoring period (June–August 2025), 402 documented cases of digital discourse containing separatist or hateful content were recorded.

3. Distribution by Platform Facebook remains the preferred platform for building ideological discourse around separation, while TikTok is the most influential in spreading symbols and images that glorify hate and division.

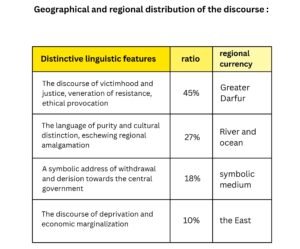

4. Geographical and Regional Distribution Darfur represents the main linguistic center for separatism, while the “River and Sea” discourse acts as a mirror reaction reinforcing regional hatred through purity vocabulary.

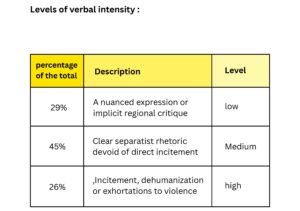

5. Levels of Discourse Intensity More than 70% of separatist discourse is presented in seemingly peaceful language but carries implicit discriminatory content, making it more acceptable and spreadable.

6. Relationship between the Two Discourses

- In 74% of cases where hate speech appears, the text also includes a reference to separation.

- In 62% of separatist texts, phrases of contempt or discrimination against an opposing group appear. This means the two discourses are intertwined to the point of being linguistically and psychologically inseparable.

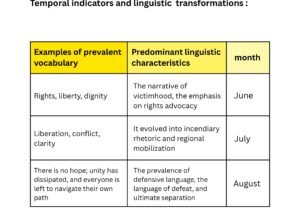

7. Temporal Indicators and Linguistic Transformations The cycle shows that separatist discourse passes through escalating emotional stages: from sadness to anger to final withdrawal.

Key Quantitative Conclusions

- Hate and separatist discourse peaked in July with a 29% increase over June.

- The relationship between hate and separatism is causal and interactive.

- The three platforms complement each other: Facebook for narrative, X for incitement, TikTok for symbolic glorification.

- The general trend indicates that separatist discourse in Sudan is transforming from a political stance into a stable linguistic structure within the public imagination.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Key General Conclusions A. Separatist discourse is a linguistic phenomenon before being political. B. Hate speech is the linguistic fuel for separatism. C. War and institutional collapse have reshaped public language. D. Digital discourse operates as a negative feedback system. E. Transformation from victimhood discourse to justification discourse.

Specific Conclusions

- Greater Darfur represents the most active expressive center using “liberation and justice” language.

- River and Sea adopted “purity and cultural distinction” discourse as a linguistic response to western discourse. 3–5. All currents share implicit contempt for the other despite differing apparent justifications.

Linguistic and Psychological Conclusion The overall dynamic can be summarized as: Separation = Hate + Symbolic Salvation + Absence of Justice Language is used here as a mechanism for psychological therapy but simultaneously deepens the collective wound.

Recommendations (As detailed in the Executive Summary and final section of the original document – repeated here in full translation above)

The language that divides can also rebuild — once it is redefined as a tool for justice, dignity, and shared living.