AR: https://kedencentre.org/2025/12/21/kanabi-in-the-crosshairs-of-hate/

Executive Summary

This report was prepared by the Kaden Center for Justice and Human Rights within the framework of the Safe Voice program, based on qualitative and quantitative analysis of hate speech directed against Kanabi communities in Gezira State, during June and July 2025, using SPSS and NVivo 14. The report aims to understand patterns of hostile discourse, its relationship to field violations, and its role in inciting violence and discrimination, while providing practical recommendations to reduce this phenomenon.

Background:

Kanabi communities in Gezira Project emerged since the beginning of the twentieth century as settlements for agricultural workers coming from Darfur, Kordofan, and West Africa, transforming over time into large residential clusters. However, Kanabi residents continued to face social discrimination and structural marginalization from some of the state’s original residents. With the escalation of armed conflict in Sudan, and the shift of control between the Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces, this discrimination transformed into systematic hate speech linking Kanabi to the military and political enemy, justifying violence against them.

Quantitative Analysis:

Statistical analysis showed that hostile discourse against Kanabi witnessed wide spread across digital platforms, especially Facebook and X (Twitter), during the monitoring period:

- Total views: approximately 14,000 views.

- Interactions: 822 interactions.

- Shares: 118 shares.

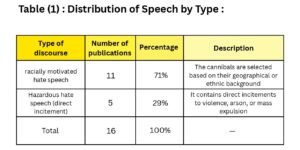

71% of discourse was ethnic in nature, and 29% was dangerous inciting discourse. The most violent discourse achieved the highest engagement and sharing rates, confirming that digital platforms have become a fertile environment for amplifying hatred and transforming it into an acceptable social narrative.

Qualitative Analysis:

The report analyzed digital texts through seven main semantic categories:

- Dehumanization and social stigmatization

- Treason accusations and linking to violence

- Incitement to violence and mass expulsion

- Demographic invasion discourse

- Land reclamation discourse

- Separatist discourse – linking Kanabi to their Darfur origins to portray them as a threat to the country

- Discourse related to rights violations – monitoring the relationship between discourse and actual incitement to killing, detention, and burning

Qualitative analysis showed that hate speech is neither spontaneous nor individual, but the product of an organized linguistic and social structure that reproduces concepts of “other,” “invader,” and “undeserving of belonging.”

Main Findings:

- Hate speech against Kanabi actually preceded and accompanied field violations including burning, arrests, and killing.

- Separatist discourse provided ideological cover for hatred, by linking Kanabi to “Darfur separation” projects.

- Hostile discourse is used to justify mass violence and reproduce regional hierarchy within society.

- Absence of organized societal response reinforces normalization of symbolic and verbal violence against Kanabi.

Recommendations:

At Legal Level:

- Applying national laws against hate speech and incitement,

- Including verbal incitement in the definition of crimes against humanity,

- Supporting efforts for legal prosecution of those inciting digital violence.

At Societal Level:

- Creating monitoring and early warning mechanisms for discourse violence,

- Launching local reconciliation programs and digital awareness to confront stereotypes about Kanabi,

- Involving tribal leaders and youth in programs combating digital incitement.

At International and Rights Level:

- Calling on UN Fact-Finding Mission to follow relationship between hostile discourse and violations against Kanabi.

- Including Kanabi communities among priority groups in humanitarian protection.

- Supporting documentation and transitional justice projects related to hate speech and incitement in Sudan.

This report emphasizes that hate speech against Kanabi is not merely a linguistic phenomenon, but part of the system of violence and discrimination in Sudan. The word has become a weapon, and discourse has transformed into a mechanism for preparation and justification of violation. Therefore, combating hate speech represents a fundamental condition for achieving justice and national reconciliation, ensuring that Kanabi’s tragedy is not repeated in any other area of the country.

Introduction

Sudan has witnessed in recent years a dangerous escalation in hate speech, which after the outbreak of war in April 2023 took more intense and polarizing forms, especially in digital spaces and social media platforms. Within this context, the Kanabi category – residential communities that historically emerged within Gezira Agricultural Project as a result of agricultural workers settling from western Sudan and Darfur – emerged as one of the most prominent targets of hostile and inciting discourse.

Posts collected from June and July 2025 reflect a repeated pattern of systematic incitement against Kanabi, combining ethnic exclusion and security and political incitement. In several texts, Kanabi are presented as a “security threat” and “haven for gangs and militias,” with explicit calls to dismantle or burn their homes, while their geographical origins are linked to the necessity of Darfur’s separation, and their presence within Gezira is portrayed as a “demographic invasion” threatening local identity.

This discourse intersects with an escalating separatist tendency invoking Sudan’s division on ethnic bases, where some speakers consider “planting Darfur’s people within Gezira” a strategic mistake, calling for “cleansing the area” through evacuation or symbolic annihilation. This is coupled with religious and moral discourse portraying Kanabi residents as “source of crime, prostitution, and alcohol,” to justify depriving them of the right to housing and belonging.

This report comes as a scientific attempt to deconstruct this phenomenon through comprehensive quantitative and qualitative analysis:

- Quantitative Analysis: Monitors distribution and types of hate speech across platforms during the target period, classifying them into ethnic, political, or dangerous discourses.

- Qualitative Analysis: Addresses semantic and linguistic structure of discourse, analyzing its relationship to political and social contexts, particularly its connection to separatist discourse and actual and potential violations against Kanabi.

The importance of this report lies not only in describing the phenomenon but in highlighting the deep structure that makes hate speech against Kanabi a tool for justifying exclusion and human rights violations. Verbal incitement in this context is not merely opinion or extreme expression, but part of a linguistic system that prepares the ground for structural and mass violence.

The report aims to contribute to building deeper understanding of the relationship between digital discourse and actual policies in Sudan, supporting rights efforts aimed at monitoring hate speech and holding its promoters accountable, protecting the social fabric and preserving the rights of all local communities without discrimination.

Historical and Contextual Background of Kanabi Communities

Kanabi are considered unique social phenomena in modern Sudan’s history, emerging in the early twentieth century with the expansion of Gezira Agricultural Project, which is the largest irrigated project in Africa, attracting tens of thousands of workers from different areas, especially from Darfur, Kordofan, and West Africa, to work in cotton cultivation and seasonal crops.

Over time, these workers’ temporary accommodation sites transformed into semi-permanent residential clusters known as “Kanabi” (singular: Kanabo), originally small huts built near agricultural plots to facilitate seasonal work.

With generational development, these Kanabi became complete communities comprising settled families, mosques, primitive schools, and vibrant social life. However, their residents continued to suffer double marginalization:

- On one hand, lack of legal recognition of their areas as official residential zones within the project;

- On the other hand, the prevailing social view among some farmers and landowners who considered Kanabi an extension of temporary migrant labor, not as an authentic community within the state.

This fragile historical situation made Kanabi vulnerable to social and class discrimination discourse for decades, but the matter took a more dangerous dimension after the outbreak of the last war in the country.

With political and field division between the army and Rapid Support Forces, some local actors found in Kanabi a ready scapegoat, as they were falsely linked to Rapid Support Forces and armed movements coming from Darfur, and discourse transformed from mere social stigmatization to incitement to killing, burning, and mass expulsion.

Historically, Kanabi represented a bridge for interaction between Sudanese cultures and regions, but today they face the danger of becoming victims of discourse that redefines citizenship itself on ethnic and regional bases.

Understanding the roots of these communities and their location in Gezira Project is not merely historical documentation but a fundamental step to explain how and why they transformed from productive labor force and important social component to subject of systematic hate speech and incitement.

Report Objectives and Methodology

First: Report Objectives

This report aims to study and analyze hate speech directed against Kanabi communities in Gezira State, by combining quantitative (statistical) analysis and qualitative (semantic and contextual) analysis, allowing understanding of the phenomenon in terms of its spread size, dynamics, and meanings.

Main objectives are:

- Monitor and analyze the size and spread of hate speech against Kanabi via social media platforms during June and July 2025.

- Classify discourse patterns into specific categories (ethnic – dangerous – inciting – political).

- Analyze linguistic and semantic content to extract expressive and symbolic features used by hostile discourse.

- Explain the relationship between hostile discourse and separatist discourse that burdens Kanabi residents with regional and political dimensions linked to their Darfur origins.

- Link hostile discourse to actual and potential human rights violations that these communities have been or may be subjected to.

- Provide practical, legislative, and media recommendations to reduce hate speech and enhance legal and societal protection for Kanabi residents.

Second: Report Methodology

1. Analysis Model

The report adopted an integrated (Mixed-Methods Approach) analysis model combining quantitative statistical analysis and qualitative structural discourse analysis, to achieve comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study.

2. Data Sources

Data was based on posts and digital content published on Facebook and X (Twitter) platforms during the period from June 1 to July 31, 2025.

The final sample included 46 posts representing explicit cases of hate speech directed against Kanabi communities.

3. Quantitative Analysis Using SPSS

Digital data was processed using SPSS statistical analysis program to extract accurate quantitative indicators including:

- Number and distribution of posts by platform (Facebook / X).

- Discourse types (ethnic – dangerous – inciting).

- Spread level in terms of views, interactions, and shares.

- Arithmetic means and standard deviation to measure differences between platforms and discourse quality.

- Correlation relationships between discourse nature and public engagement level.

4. Qualitative Analysis Using NVivo

NVivo 14 was used to conduct in-depth semantic and contextual analysis of text data according to Content Analysis methodology.

A coding system (Codebook) was built including thematic and linguistic categories representing main patterns in discourse.

Qualitative analysis relied on repetition and semantic saturation to extract relationships between categories, tracking recurring vocabulary and structures (such as: “burn,” “strangers,” “23 cannon,” “expulsion”) to determine symbolic structure of violence within used language.

5. Credibility and Reliability Verification

- Internal validity: Through double review of coding in NVivo and comparing results between independent analysts to ensure consistency.

- External validity: By matching qualitative results with quantitative indicators resulting from SPSS to prove connection between numerical spread and discourse intensity.

- Field verification: Some results were reviewed with field monitors in Gezira State to confirm accuracy of their social and political context.

6. Ethical Controls

- Account identities and personal names were concealed to protect individuals from retaliation or stigmatization.

- Quotations from original posts were used for analytical purposes only, without republishing any inciting content.

- The report adheres to research transparency principles and non-bias, adopting ethical standards in analyzing sensitive digital data.

7. Report Limitations

- Report covers limited time period (two months), making its results general indicators subject to future update.

- Only text content was analyzed without including images or video clips, despite their growing role in incitement.

- Report does not address official discourse of political institutions but focuses on popular discourse in digital space.

Third: Added Value

This report represents an applied model combining statistical and linguistic analysis of digital discourse in Sudan, thus providing an original contribution in linking scientific analysis to human rights discourse.

It also serves as a practical tool that can be used later to develop a national hate speech indicator, establishing an early warning mechanism for identity-based violence.

Quantitative Analysis

Overview of Data

Quantitative analysis in this report relied on processing digital data extracted from public posts on Facebook and X (Twitter) platforms during June and July 2025, which included explicit content of hate speech directed against Kanabi communities in Gezira State.

The number of cases monitored and analyzed reached 46 posts, representing clear examples of repeated and influential hostile discourse.

This data was processed using SPSS to extract accurate quantitative indicators, including: number of posts, discourse type, platform, and number of views, shares, and interactions.

Discourse Distribution by Type

Analysis results showed that ethnic discourse is the most common pattern in posts directed against Kanabi, constituting about 71% of total monitored content.

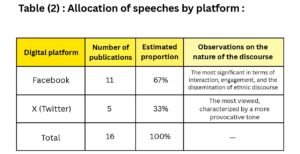

Distribution by Digital Platforms

Analysis revealed that Facebook was the most prominent space for hostile discourse spread, capturing about two-thirds of monitored posts, with engagement rates exceeding X platform.

This is attributed to the social nature of Facebook users in Sudan, and the wider circle of comments and shares compared to X space, which is dominated by elitist political discussion.

It was also noted that Facebook posts receive greater engagement in terms of number of shares and comments, while content published on X achieves relatively higher viewing rates but is lower in direct engagement.

This indicates that hate speech on Facebook penetrates local communities more deeply, while spreading on X among circles more connected to public and political discussion.

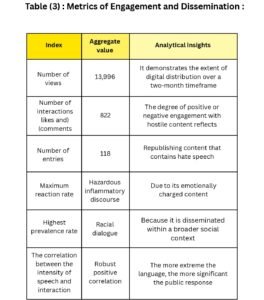

Engagement and Spread Indicators

Total views during the monitoring period after multiplication reached approximately 13,996 views, a figure reflecting the digital spread size of hostile discourse against Kanabi in just two months.

Total interactions (likes, comments, emojis) reached 822 interactions, while 118 direct shares of content including incitement or collective stigmatization were recorded.

These figures indicate that hostile discourse against Kanabi is not marginal, but enjoys considerable degree of circulation and sharing, especially in posts combining ethnic and inciting elements, as this type of discourse tends to achieve higher engagement rates due to its emotional and passionate nature.

Relationship Between Discourse Type and Engagement Level

Statistical analysis showed a positive correlation between discourse intensity and public engagement level, as posts with violent or inciting language achieved the highest sharing and commenting rates.

This confirms that the most extreme discourse is also the most attractive for digital engagement, reinforcing the hypothesis that social media networks contribute — through algorithm mechanisms — to amplifying hostile discourse instead of limiting it.

In contrast, posts containing implicit ethnic insinuations or sarcastic mockery showed lower engagement rates, but are more spread in terms of negative circulation (quoting or reposting without comment).

General Digital Indicators

Quantitative indicators show that hate speech against Kanabi:

- Tends to wider spread on platforms with local social character (Facebook).

- Is characterized by ethnic nature more than direct inciting nature, reflecting that the fundamental root of discourse is identity discrimination, not direct political incitement.

- Transforms in some cases into explicit calls for mass violence, making its dangers exceed the verbal framework to the possibility of actual incitement.

- Enjoys relatively high engagement degree, meaning this type of discourse is not met with general rejection, but finds a sympathetic or silent environment toward it.

Conclusion

Quantitative analysis highlights that hate speech against Kanabi in Gezira State is an escalating and systematic phenomenon, feeding on social and political divisions produced by armed conflict in Sudan.

Discourse is no longer merely expression of opinion or position, but has become a tool for criminalizing an entire population group, justifying violence against them and reproducing old social stigma in new form.

These results are a dangerous indicator that digital space has become a fertile environment for reproducing discrimination, and that addressing this phenomenon requires multi-level intervention — legal, media, and educational — aimed at weakening digital incitement structure before it transforms into material violence.

Qualitative Analysis:

Semantic and Linguistic Patterns of Hate Speech Against Kanabi

Qualitative analysis aims to understand the deep structure of hostile discourse directed against Kanabi communities, in terms of language, symbols, and meanings it relies on in justifying hatred and exclusion.

While quantitative data shows discourse spread size, qualitative analysis reveals how this discourse is linguistically and semantically constructed, and how it produces social and political perceptions contributing to legitimizing violence or discrimination against a specific population group.

Analysis relied on a detailed coding system (Codebook) within NVivo, comprising seven main semantic categories, five of which are basic hate speech patterns, and two interpretive ones reflecting the relationship between discourse and social and political reality.

1. Dehumanization and Social Stigmatization

This pattern is one of the most repeated and common discourse patterns.

It manifests in using derogatory terms stripping Kanabi of their human qualities or portraying them as a degraded or backward category.

Descriptions like “drunkards,” “slaves,” “filth,” “strangers” are repeated, words historically used in Sudan to consolidate social hierarchy and class discrimination.

This pattern leads to stripping human empathy with victims, where Kanabi are not viewed as individuals equal in dignity, but as “other” of lower status, who can be mocked or expelled without guilt feeling.

This type of discourse represents the first linguistic entry to violence, as it prepares psychologically and socially to justify violation.

Discourse here deliberately merges ethnic features and moral qualities into one image, to form a “stereotypical personality” for Kanabi: “strangers” are “drunkards,” and “criminals” are “slaves.”

That is, geographical or ethnic affiliation is implicitly equated with moral deviation.

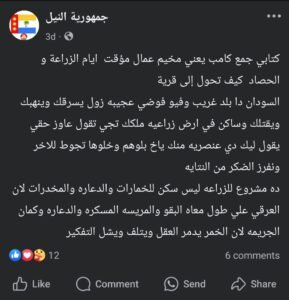

Example (1):

2. Treason Accusations and Linking to Armed Violence

This pattern manifests in directly linking Kanabi to Rapid Support Forces or armed movements coming from Darfur, accusing them of being sleeper cells or cooperating elements.

This accusation is used to justify arrest and burning operations, by spreading narratives like:

- “These are Rapid Support Forces soldiers in disguise,”

- “They are the ones who guided Janjaweed to citizens’ homes,”

- “Most Kanabi have weapons and rebels”

This pattern links regional identity to a crime presumed in advance, transforming population presence itself into a security threat.

In semantic analysis, it is noted that discourse uses plural pronouns (“they”) versus “we” to produce enemy/victim duality, entrenching social division between Gezira residents and Kanabi.

This pattern is considered most dangerous from a rights perspective, because it strips legal legitimacy from Kanabi as citizens, opening the door to targeting them under the pretext of “national security.”

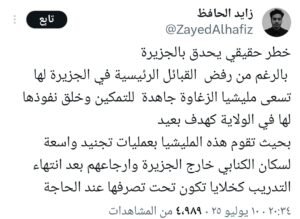

Example No. (2)

3. Incitement to Violence and Mass Expulsion

This pattern is the most direct and dangerous, where discourse transforms from verbal exclusion to explicit calls for action.

Expressions appear like:

- “Burn them before they return,”

- “Clean Gezira from strangers,”

- “Kanabi must all be removed.”

This discourse is not content with incitement but shows normalization of violence as a legitimate option, using collective vocabulary (“clean,” “protect”) to give false national dimension to exclusion act.

This pattern is linked to moments of political and field tension, especially during control shift between army and Rapid Support Forces in Gezira State, where digital discourse transforms into psychological catalyst for societal violence.

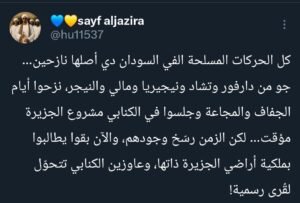

Example No. (3)

4. Demographic Invasion Discourse

Kanabi here are portrayed as “population invaders” threatening social and demographic balance in Gezira.

Phrases are used like:

- “They occupied our lands,”

- “Their number increased until they became country owners,”

- “Strangers controlled all projects.”

This pattern expresses collective fear more than being direct incitement, but is more dangerous in terms of rooting structural racism, because it portrays Kanabi’s very existence as a threat that must be dealt with.

It leads to justifying any form of exclusion (such as preventing housing or education) as a preventive measure.

This discourse is based on implicit colonial metaphor: “invaders,” “occupation,” “settlement,” stripping Kanabi of any right to local existence, reproducing the concept of “invading other.”

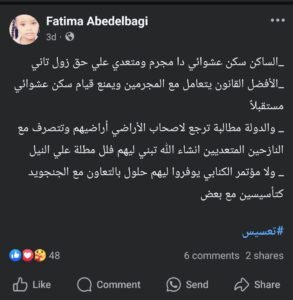

Example No. (4)

5. Land Reclamation Discourse

This pattern focuses on demanding Kanabi expulsion on the pretext that land belongs to Gezira people and Kanabi are “intruders who seized plots.”

The term “land reclamation” or “project cleaning” is repeated in posts, language that mimics sovereignty and entitlement vocabulary.

In essence, discourse does not talk about “legal ownership” but about land identity, where ownership becomes justification for excluding an entire group.

Thus discourse transforms from economic demand to racist tool redefining who deserves land and who doesn’t.

Example No. (5)

6. Separatist Discourse

This interpretive pattern emerges in the way Kanabi are linked to “Darfur” as a geographical root outside local belonging.

This link is used to frame Kanabi as a non-belonging group to the state or homeland, through phrases like:

- “Leave Darfur to its people,”

- “Return to your country,”

- “Strangers want to make another state.”

Clear convergence appears here between hate speech and political separation discourse, where Kanabi are framed as part of “strange project” threatening Sudan’s unity.

This formula opens the door to denying citizenship and stripping Kanabi of their constitutional rights through regional hostility language.

7. Discourse Related to Human Rights Violations

Through linking qualitative analysis and field monitoring, it was evident that hostile discourse against Kanabi preceded and accompanied actual violence operations including killing, burning, and mass detention.

Hate speech was used as social justification tool for these violations, presenting violence as “legitimate reaction” or “land defense.”

Also, continuation of circulating hostile discourse with same linguistic structure after those violations suggests likelihood of their repetition in the future, as it was not met with wide societal rejection discourse.

Therefore, this pattern represents a bridge between discourse and action, highlighting how words can become preludes to crime.

Conclusion

Qualitative results reveal that hate speech directed against Kanabi is neither spontaneous nor individual, but the product of a repeated linguistic and social structure based on:

- Established perceptions about “Darfur other,”

- Long discriminatory legacy in Gezira Project,

- Feeds today from political and military division state.

Language in this discourse is not merely a means of expression, but a tool for domination and symbolic control, redefining who is “citizen” and who is “invader,” implicitly justifying violence and exclusion in the name of protecting the original group.

Relationship Between Hate Speech Directed Against Kanabi and Separatist Discourse

Qualitative analysis results show that a large part of hate speech directed against Kanabi in Gezira State cannot be separated from separatist discourse with regional and political roots linked to Darfur region.

The geographical origin of a large number of Kanabi residents — whose ancestors moved to Gezira Project for work since the beginning of the twentieth century — has today become a symbolic framing tool used to accuse them of lacking full national belonging, or loyalty to assumed “separatist” projects.

This linking between “Darfur origin” and “separation” represents a linguistic and political mechanism for producing hatred, presenting Kanabi as “strangers” carrying existential threat to state entity and regional unity.

First: From Regional Identity to “Political Threat”

Hostile discourse usually starts from simple ethnic or regional discrimination (“these are from Darfur”), then gradually escalates to become political accusation (“they are followers of movements,” “they are those who want to divide Sudan”).

With this gradation, regional identity is transformed into political charge, then into social justification for violence and exclusion.

Through analyzing sample posts in NVivo, expressions were repeated like:

- “These are intruders from Darfur,”

- “They have an invasion project from the West,”

- “These strangers want to rule the country,”

- “Kanabi are part of a large Darfur plot.”

This language does not attack Kanabi as individuals but presents them as an integrated geographical-political component, meaning as “threat group” representing collective danger to regional unity.

This leads to deliberate confusion between geographical affiliation and political loyalty, one of the most prominent characteristics of separatist discourse in Sudan since the beginning of the millennium.

Second: Mobilization Function of Separatist Discourse

This type of discourse plays a dual inciting role:

- Stimulating local hatred by portraying Kanabi as external force seeking to seize land.

- Redefining national belonging from narrow regional perspective, making “original Gezira person” versus “Darfur intruder.”

Data showed that many posts linked Kanabi to:

- Rapid Support Forces (as Darfur origin),

- Armed movements,

- Or “West Sudan state” project.

Thus separatist discourse transforms into justification umbrella for violence: where crimes against Kanabi are portrayed as “defensive measures” against state dismantling project or “Gezira colonization from the West.”

Third: Linguistic Structure of Separatist Discourse

Linguistically, this discourse is characterized by three main features:

- Using identity division pronouns: Words like “we Gezira people” versus “they are strangers,” establish “original/intruder,” “national/invader” duality.

- Political war metaphors: Using vocabulary like “invasion,” “settlement,” “Darfur occupation,” metaphors transforming population presence into hostile act requiring resistance.

- Reference to geographical separation: Phrases like “return to your country,” “leave Darfur to you,” “you won’t divide Sudan on us,” used to deny national belonging and assign exclusive geographical identity to Kanabi.

These features make separatist discourse complementary to hate speech in terms of function, but deeper in terms of impact because it strips legitimacy of citizenship itself, not merely social coexistence.

Fourth: Social and Political Impact of Discourse

The relationship between hate speech and separatist discourse shows that both work in one direction:

- Preparing to legitimize exclusion and violence.

- Feeding regional division in Sudan.

Through this discourse, the concept of “national identity” is reproduced on exclusionary basis, where “who belongs to the homeland” is redefined according to origin and place logic, not according to law and citizenship.

This linguistic transformation translates in reality into grave violations like arrests, burning, and mass expulsion, which were later documented against Kanabi.

In other words: Separatist discourse does not express political opinion but an exclusionary structure attempting to exclude a human group from national belonging space, using hate speech as emotional catalyst and social justification.

Interpretive Implications

Through linking qualitative and quantitative analysis, three main implications can be drawn:

- Hate speech against Kanabi is a tool for entrenching regional separation narrative, not merely a passing social position.

- Inciting language (“return to your country”) forms a direct link between digital discourse and actual violations, as it justifies actions under cover of “homeland defense.”

- Separatist discourse is the deep ideological component of hate speech against Kanabi, giving it symbolic legitimacy and transforming it from insult to “national task.”

It can be said that separatist discourse is not merely a supportive context for hate speech but its intellectual infrastructure.

Separation in this context is not understood geographically only, but symbolically: separation from citizenship, from rights, and from human equality.

When Kanabi’s existence is linked to “Western” or “Darfur” projects, this does not aim at political discussion but at legitimizing their expulsion from the state and society.

Therefore, this axis represents one of the most dangerous levels of hate speech in Sudan, because it transfers hostility from social domain to national and sovereign domain, transforming difference in origin into existential threat to the state.

Relationship Between Hate Speech and Human Rights Violations Against Kanabi Residents

Comparison between digital discourse content directed against Kanabi residents and field facts witnessed in Gezira State during June and July 2025 reveals that hate speech was not merely verbal or emotional expression, but played a direct role in preparing psychological and social ground for grave violations affecting these communities.

Hostile discourse — especially on social media — represented the stage of “symbolic normalization” of violence, meaning transforming violence from condemned behavior to morally acceptable and justified act in collective imagination.

First: From Word to Action

Analysis of chronological sequence of posts showed that hostile discourse against Kanabi actually preceded the first wave of arrests and burning that occurred in several villages after Armed Forces’ control of Gezira State.

In the weeks preceding those events, posts and digital clips spread using inciting language like:

- “Clean Gezira from strangers,”

- “Kanabi are Rapid Support Forces weapons stores,”

- “Burn them before they betray you.”

This language — as analysis in NVivo showed — was characterized by three escalating stages:

- Stereotyping and distortion stage: Dehumanization and linking Kanabi to crimes.

- Community mobilization stage: Calls for collective action to expel or fight Kanabi.

- Moral justification stage: Considering violence “land defense” or “national duty.”

Thus, violent act does not become deviation from discourse but its fulfillment, where hate speech transforms into systematic mobilization and incitement tool.

Second: Incitement and Justification Mechanisms

Hostile discourse relied in building its legitimacy on three main linguistic and semantic mechanisms:

- Imagined security threat: Portraying Kanabi as danger source to local stability (“Rapid Support Forces cells,” “weapon camps”). This security imagination created advance justification for collective punishment.

- Moral and religious invocation: Linking violence to the idea of “protecting land and honor,” or “cleansing Gezira from evil,” giving violence false moral and religious legitimacy.

- Redefining victim and aggressor: In hostile discourse, original Gezira residents are presented as potential victims, while Kanabi are portrayed as aggressors, Thus killing them or burning their villages becomes legitimate defense act.

Language transforms from describing reality to producing it: when it is said that Kanabi “control the project,” it is not a descriptive sentence but an implicit call “to reclaim it.”

Thus, the word becomes an executive signal for violence, not merely discourse.

Third: Discourse Reflection in Field Violations

According to information documented by Safe Voice program and local testimonies from Gezira, some Kanabi communities during that period were subjected to:

- Systematic village burning operations,

- Wide-scale arbitrary arrests,

- Identity-based killing operations,

- Forced displacement of entire families.

This violation pattern matches the discourse structure that preceded it, showing that hate speech formed the justification framework for violence.

Each qualitative discourse category had a specific actual impact:

- “Dehumanization” discourse paved way to justify killing.

- “Security threat” discourse justified mass detention.

- “Land reclamation” discourse legitimized burning and displacement.

Fourth: Ongoing Psychological and Social Impact

Hostile discourse impact is not limited to the moment violence occurs but extends in form of collective trauma and renewed marginalization.

Kanabi today face double stigma:

- Ongoing digital stigma via social media,

- Field social stigma reflected in discrimination in work, education, and housing opportunities.

This situation leads to reproducing fear and isolation within these communities, undermining future reconciliation opportunities, because hatred has not been addressed discursively yet but is still being reproduced in digital space.

Fifth: Legal and Rights Consequences

According to international human rights law standards, hate speech leading to incitement or public justification of violence can be considered indirect participation in crime if causal relationship between discourse and action is proven.

In Kanabi’s case, qualitative and quantitative analysis shows that inciting content played pivotal role in shaping societal climate that allowed violations to occur.

Based on this, hate speech should be viewed as one of the violation mechanisms itself, not only as linguistic phenomenon, because it contributes to producing an environment accepting discrimination and collective punishment.

Sixth: Early Warning Indicators

Through analyzing linguistic and symbolic trends in posts, several warning patterns indicating likelihood of future violation escalation can be identified, including:

- Increased use of “cleansing,” “reclamation,” and “duty” vocabulary in digital discourse.

- Rising engagement rates with posts linking Kanabi to “security threat.”

- Increasing informal collective calls for punishment or evacuation.

These indicators can form basis for building monitoring and early warning system for societal violence relying on discourse analysis.

Conclusion

Qualitative results reveal that hate speech against Kanabi is the linguistic passage to actual violence.

The word was the beginning of the crime, and language was its moral cover.

It is clear that this discourse led to:

- Preparing local public opinion to accept violations,

- Stripping victims of humanity and collectively criminalizing them,

- Legitimizing violence through false national or religious narratives.

Therefore, violations cannot be addressed without addressing their discursive roots, and justice cannot be achieved without holding accountable those who used the word as an incitement tool for symbolic and material annihilation against Kanabi community.

Conclusions, Recommendations, and Conclusion:

This report, based on analyzing quantitative and qualitative digital data, reveals that hate speech directed against Kanabi communities in Gezira State represents one of the most dangerous manifestations of societal incitement in the context of current Sudanese war.

Quantitative analysis showed wide spread scope of hostile discourse on social media platforms, while qualitative analysis clarified that this discourse enjoys organized linguistic and methodological structure transforming it from individual opinion to systematic tool for violence and discrimination.

The report highlights that the relationship between discourse and violations is not merely temporal succession relationship but direct causal relationship: hostile discourse precedes field actions, justifies them after occurrence, and prepares for their future repetition.

Main Conclusions

- Hate speech against Kanabi is structural, not circumstantial in nature Discourse transcends temporary reaction stage to being an extension of historical discrimination structure in Gezira Project, based on hierarchical perceptions about “original” and “intruder.” Therefore, hatred roots are not war products, but war enabled transforming it into effective political and social tool.

- Ethnic discourse is the dominant form of hatred Ethnic discourse constituted more than 70% of total hostile content, indicating that hatred is built on identity and regional affiliation more than any other factor, with invoking words and stereotypical images rooted in local culture.

- Inciting and dangerous discourse is more influential in terms of engagement and spread Although its percentage is lower (about 30%), direct inciting discourse enjoys greater public engagement and achieves wider spread thanks to digital platform algorithms that reward exciting and emotionally charged content.

- Relationship between hate speech and violations is causal and direct Temporal and semantic analysis proves that hostile discourse preceded killing, burning, and mass detention incidents targeting Kanabi residents, making discourse itself a contributing element in producing violation, not merely its reflection.

- Separatist discourse represents the ideological framework for hatred Linking between Kanabi and Darfur is used to justify denying their citizenship and considering them a threat to national unity. Thus, separatist discourse transforms into political and social cover for hate speech, doubling its danger to national fabric.

- Digital space is the central driver of hostile discourse Facebook specifically was the most active platform, where local communities circulate hate

speech in formats closer to daily conversation, making its impact deeper in actual social environment.

- Hostile discourse is ongoing and has not been faced with organized societal rejection Despite violations’ gravity, no strong counter-discourse appeared enhancing coexistence and citizenship values, indicating partial normalization of verbal and symbolic violence against Kanabi in local public consciousness.

Recommendations:

1. At Legal Level

- Expediting application of national and international laws specific to combating hate speech, activating penalties against those publishing or promoting inciting content via digital platforms.

- Including explicit verbal incitement within the definition of crimes against humanity when leading to actual violations.

- Supporting Public Prosecution and human rights organizations’ efforts in documenting relationship between discourse and violation to establish legal cases against inciters.

2. At Media Level

- Preparing media and digital conduct codes to confront hate speech on local platforms.

- Launching digital awareness campaigns in local language targeting agricultural communities and Kanabi residents to enhance “equal citizenship” discourse.

- Training journalists and bloggers to distinguish between critical coverage and inciting discourse.

3. At Societal Level

- Enhancing local dialogue and social reconciliation programs between agricultural village residents and Kanabi communities.

- Creating community mediation committees including tribal and religious leaders and youth to confront rumors and incitement.

- Supporting early warning initiatives for societal violence by monitoring linguistic indicators of incitement on platforms.

4. At Research and Academic Level

- Continuing hate speech analysis in other areas of Sudan to form national database about regional hostility patterns.

- Developing automatic linguistic analysis tools capable of detecting inciting words and vocabulary in real time.

- Integrating discourse, hatred, and human rights topics into media, sociology, and politics faculties’ programs in universities.

5. At Humanitarian and Rights Level

- Documenting Kanabi survivors’ testimonies within national database for transitional justice.

- Providing psychological and social support to victims and their families within community reintegration programs.

- Demanding UN Fact-Finding Mission to follow relationship between hostile discourse and field violations in Sudan as priority in its work.

Conclusion

This report emphasizes that the word in current Sudanese context is no longer merely expression tool but has become a linguistic weapon producing violent action.

Hate speech against Kanabi does not reflect a communication crisis but a justice and national identity crisis, manifesting historical accumulations of social and economic discrimination.

Therefore, confronting hatred cannot be only security-related but needs deep treatment of its social and economic roots, rebuilding public consciousness on the basis of equal citizenship and human dignity.

Justice does not begin with accountability only but begins first with breaking the silence of language that justifies injustice.