AR: https://kedencentre.org/2025/12/26/safe-voice-accounts-under-the-microscope-december/

Introduction

“From Monitoring to Reading the Digital Memory of Hatred”

November monitoring results, covering thirty accounts on X, Facebook, and TikTok platforms, reveal that hate speech in the Sudanese space is no longer measured by the amount of content published during a specific period, but by its ability to continue over time and regenerate. Materials analyzed in this edition mostly belong to past time periods, but remained active and influential due to continuous republishing and circulation, making digital hatred a phenomenon transcending the moment to what can be called “hostile discourse memory.”

Data analysis showed that hostile content did not disappear with the passage of its temporal context, but transformed into a symbolic repository recalled whenever political or military crises renew. The old tweet is retrieved in a new moment of anger, and the video clip used in a regional context a year ago is republished today with the same hostile charge, even if the apparent meaning has changed. In this way, platforms transform into a dynamic archive of verbal violence that recycles hatred instead of weakening it.

This edition clarifies that understanding hate speech today requires moving from analyzing “the post” to analyzing “time,” and from tracking the word to tracking its age and circulation path. The basic indicator is no longer the number of posts or their intensity, but the extent of their ability to survive digital time and renew in new contexts.

Comparison between the three platforms also reveals that digital time of hatred is unequal:

- On TikTok, hostile discourse renews through re-mixed clips and audio remixes that give old content a modern appearance.

- Facebook recycles old controversial posts in the form of new collective discussions.

- While X works as a repository for political archive of hostility, from which tweets are retrieved whenever an event or crisis escalates.

Based on this, this issue of “Accounts Under the Microscope” focuses on analyzing time dynamics in hate speech: how hostile content lives after its time, how its meanings change when republished at different moments, and what this means for the future of digital discourse in Sudan.

What we monitor today is not merely hatred being spoken, but hatred that remembers and reproduces itself, lives between times and changes its faces with each republication.

Methodology

“Two Times for Discourse… and One Time for Analysis”

The Safe Voice program team in preparing the December edition of “Accounts Under the Microscope” newsletter relied on a dual analytical approach combining quantitative monitoring of hostile content and qualitative analysis of temporal and symbolic contexts, aiming to track hate speech continuity across different time periods and understand how it is reproduced in new contexts.

This edition covers surveillance results conducted during November 2025, on a sample comprising thirty active accounts distributed across three main platforms:

- 14 accounts on TikTok

- 8 accounts on Facebook

- 8 accounts on X

However, analyzed content is not limited to what was published in November, but extends to past time periods; it included posts and video clips that were re-circulated or users recently interacted with, allowing tracking of discourse evolution over time and analyzing digital memory of hatred.

First: Data Collection

Monitoring process was conducted using digital tools for systematic monitoring and data preservation, with strict adherence to privacy standards and research ethics.

Collection process included:

- Documenting most repeated or re-circulated posts and clips.

- Determining original periods of content publication and comparing publication time with last interaction time.

- Coding content according to discourse type (ethnic, political, or dangerous) and language nature (explicit, symbolic, sarcastic).

Second: Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis was based on measuring digital performance indicators of hostile content, including:

- Number of hostile posts from total content published in each account.

- Engagement rates (comments, likes, shares) during monitoring period.

- Percentage of content re-circulated from previous periods.

- Platform distribution of hostile discourse and its temporal indicators.

This data was entered into dedicated analytical tables to estimate the size of temporal circulation of hatred and identify platforms most lenient in republishing inciting content.

Third: Qualitative Analysis

The team relied in the qualitative aspect on content analysis and linguistic and semiotic context, focusing on three levels:

- Time: Studying differences between original publication time and re-circulation time, and their impact on meaning and significance.

- Symbol and discourse: Analyzing vocabulary, slogans, and cultural symbols that give hostile discourse its renewable character.

- Stylistic transformations: Tracking how language moved from frankness to insinuation, and from direct insult to implicit sarcasm.

This qualitative analysis allowed understanding how hatred transforms from an immediate linguistic phenomenon to an extended narrative structure that recalls itself over time.

Fourth: Verification and Review

Each analyzed content underwent collective review within the research team, to ensure classification accuracy and interpretation credibility, comparing it with results from the previous November edition.

The principle of “temporal matching” between digital and textual data was also adopted to verify publication context accuracy, preventing confusion between original and recycled content.

Fifth: Methodology Objective

This methodology aims to transcend momentary monitoring toward analyzing the temporal and symbolic structure of hate speech, meaning understanding how hatred is reproduced not as a temporary event, but as a renewed communicative path where language interacts with memory, algorithm, and audience over time.

Discourse Trends Over Time

“From Explicit Hatred to Renewed Symbolism”

Temporal analysis results showed that hate speech in Sudanese digital space is no longer an intermittent event, but a continuous narrative system that adapts to changing events and reproduces itself over time and platforms. Old content does not die but is retrieved and transforms to keep pace with current political and social mood.

This manifests in a set of discourse transformations expressing hatred’s transition from frankness to camouflage, and from direct attack to building deeper symbolic narratives.

First: Archived Incitement – Hatred That Does Not Die

One of the most prominent trends is represented in old content returning to circulation after long periods since publication, especially in moments of field escalation or political tension.

Clips and tweets published a year ago or more were republished as if new, to be used as evidence or mobilization slogans.

This phenomenon transformed platforms into “hostility stores,” where TikTok and Facebook algorithms work to revive discursive memory instead of weakening it.

Thus, hostile discourse acquired temporal permanence transcending the event, living and being recycled whenever a new crisis erupts.

Second: Transition from Explicit Hatred to Symbolic Sarcasm

Many posts re-circulated during the monitoring period were found not to have direct content or sharp language, but presented hatred in sarcastic or lyrical formats.

- On TikTok, sarcastic clips transformed into an effective means of passing collective insult under the cover of humor or “political entertainment.”

- On Facebook, comics and symbolic images were used to embody ethnic or political hostility in a light but negatively loaded way.

- On X, implicit political analysis and black sarcasm became the most common form of inciting discourse.

This transformation indicates new linguistic intelligence in expressing hatred, where symbolic violence is passed in more socially acceptable ways and more difficult to monitor.

Third: Changing “Enemy” Image Over Time

Data shows that defining “enemy” in hostile discourse is no longer fixed but changed according to conflict transformations.

- In war beginnings, the enemy was presented as political groups (Kezan – FFC).

- Over time, discourse expanded to include regional or ethnic categories, especially in Darfur and Kordofan posts.

- Recently, a new form of “symbolic hostility” appeared targeting professional or civilian groups as “defeatist” or “neutral.”

This development reflects hatred’s transformation from defined enemy to imagined enemy — meaning to an exclusionary thinking pattern that reproduces itself in any circumstance.

Fourth: Religious and Patriotic Camouflage of Hatred

An increasing trend emerged toward using religious and patriotic discourse as cover for incitement.

Vocabulary like “jihad,” “martyrdom,” “defending honor,” and “love of homeland” are used to justify verbal or material violence against opponents.

This pattern does not directly announce hatred but presents it as a “moral duty.”

Thus, religious language transforms into a mechanism for beautifying violence, and patriotic symbols into an ideological shield for hatred.

Fifth: Narrative Transformation from Confrontation to Justification

Some accounts — especially on Facebook — show posts expressing consciousness transformation from incitement to justification.

Discourse no longer focuses on “explicit hostility” but on justifying hatred as a result of “betrayal,” “historical grievance,” or “natural response to insult.”

This language shows that hostile discourse has become more psychologically and culturally complex, mixing victim and perpetrator in one narrative.

Sixth: Geography’s Continuation in Producing Hatred

Despite stylistic transformations, the regional and ethnic dimension still constitutes the most entrenched constant in digital hatred structure.

Regional and tribal names are used as symbols of identity or betrayal.

Many narratives are built around the idea of “land reclamation” or “area cleansing.”

This trend clarifies that mental maps of hatred still govern Sudanese digital space, even if their vocabulary and masks have changed.

Conclusion

These trends highlight that hate speech in Sudan lives within multi-layered time:

- Original publication time,

- Renewed circulation time,

- And collective memory time that recalls hostility whenever the event changes.

In this sense, hatred is no longer merely immediate discourse but has become a renewed emotional and political archive, recycled in symbolic and semiotic ways that preserve its impact and increase its social depth.

Understanding this temporal extension is key to understanding incitement nature in Sudan today, where hate speech is born not only from conflict but from a long memory that does not forget.

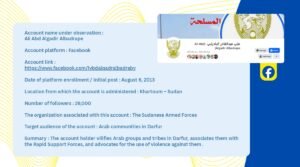

Review of Accounts Monitored During November:

TikTok:

Facebook:

Twitter:

Comparative Quantitative Analysis

“When Numbers Create Digital Memory Map”

Statistical processing of data extracted from thirty accounts monitored during November 2025 showed that Sudanese hate speech is characterized by continuity more than renewal; more than half of hostile content circulated during the monitoring period was copied or republished from previous materials, confirming the “hatred memory” hypothesis that formed the focus of this edition.

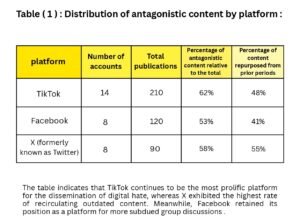

Total analyzed materials exceeded 420 posts and video clips, distributed among the three platforms as follows:

The table shows that TikTok platform still represents the most fertile environment for circulating digital hatred, both in terms of size and spread speed, while X platform was distinguished by the highest percentage of old content re-circulation, making it the most prominent platform in reviving archived discourse and re-entering it in new contexts.

Facebook retained its role as a space for long collective discussions, but with a decline in discourse intensity compared to previous months, in favor of more “analytical” and less direct incitement language.

1. Digital Engagement Rates

Data showed that hostile content not only achieves high spread but also garners 37% greater engagement compared to regular content, especially on TikTok.

- Short hatred clips with sarcastic character were the most circulated, with sharing rate ranging between 2.5 to 3 times the general engagement average.

- On X, old tweets that were republished garnered new interactions at 20% of total recent comments, reflecting the power of “deferred time” impact.

- On Facebook, discussions under old shared posts constituted about a third of total engagement, indicating discourse continuation despite content aging.

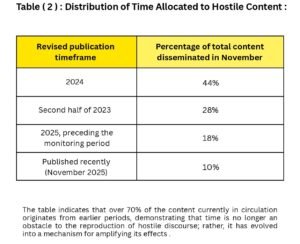

2. Temporal Distribution of Hostile Discourse

Comparing original publication dates with re-interaction times shows that digital hatred transcends linear time boundaries:

Table No. (2)

This distribution proves that time is no longer a barrier to hostile discourse reproduction; it has become a tool for intensifying its impact through continuous past recall.

3. Nature of Hostile Content

When classifying hostile materials by type, the following emerged:

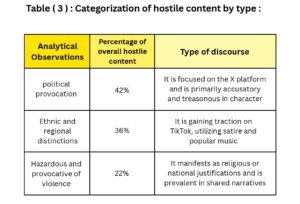

Table No. (3)

This distribution shows that political and regional discourse remain the basic drivers of digital hatred, while “dangerous” direct discourse declines toward camouflaged and more symbolic forms.

4. Comparison with Previous November Edition

Compared to November results:

- Overall hostile content percentage increased by about 8%, although most materials are not new.

- Explicit content percentage declined from 58% to 46%, versus clear rise in sarcasm discourse and disguised incitement.

- Recycling rates (republishing or quoting) nearly doubled, especially on TikTok and X.

- Multi-platform content appearance rate (shared across more than one platform) increased from 19% to 31%.

5. Quantitative Implications

These figures reveal that hate speech in Sudan has become a repetitive communication system more than a momentary reaction.

Hostile content moves between platforms and is recycled according to algorithms preferring “exciting and polarizing,” giving it longer life and wider impact.

Also, the widening time gap between first publication and re-circulation reflects declining effective censorship of old content, and rising users’ ability to exploit it politically or emotionally in each conflict cycle.

Conclusion

It can be said that hate speech in Sudan has entered the sustainable spread phase:

- It is no longer measured by quantity only, but by its ability to survive and be recalled.

- Platforms are no longer merely publication tools but digital preservers of hostile memory.

- Hatred here is not renewed as much as it is continuous and transforming, moving from one time to another as it moves from one account to another, preserving its roots even if it changes its appearance.

Qualitative Observations

“Hatred That Masters Survival: Observations on Discursive Recycling”

Through qualitative analysis of content monitored during November — covering time periods extending from 2023 to 2025 — it became clear that hate speech in Sudanese space is no longer merely expression of anger or momentary mobilization, but has become a renewed linguistic and cultural phenomenon that reproduces itself through new tools and methods.

Following are the most prominent qualitative observations reflecting this transformation:

1. Recycling as Mobilization Mechanism

Monitoring showed that many accounts — especially on TikTok and X — practice what can be described as “inciting recycling”; old clips and posts are republished in tense political or military moments to restore their original mobilization impact.

This behavior indicates strategic awareness of using digital memory, where the past is employed as a permanent mobilization reserve.

In other words, hatred is no longer born of the moment but has become a “ready-to-use warehouse on demand.”

2. Loss of Original Context of Content

Analyses highlighted that most re-circulated posts are presented without their original temporal or factual context, creating distortion in collective memory.

Old clips from previous conflict areas are published as if current events.

Tweets from a different phase are used as evidence in new discussions.

As a result, hatred transforms into timeless discourse, losing its relationship to the event but retaining its emotional charge.

3. Normalizing Insult and Reproducing Hostile Vocabulary

The team noted that repeating hostile vocabulary over approximately two years made some phrases part of users’ daily language.

Words like “slaves,” “Kezan,” “Jellaba,” and “fifth column” became used without surprise or disapproval.

This linguistic normalization makes hatred less conscious and more entrenched.

Language here is no longer merely a tool for expressing hatred but has become a space that continuously reproduces it.

4. Emergence of “Hostile Comedy”

Transforming sarcasm into a means of expressing anger and division is one of the most important new qualitative features.

- On TikTok, hostile discourse is presented in sarcastic clips or symbolic dances employing popular music in mocking opponents.

- On Facebook, political jokes and sarcastic images are used as alternatives to direct hate speech.

This comedy gives hostile discourse wide social acceptance because it lightens its linguistic intensity without touching its inciting content.

5. Hatred Masked as Political Analysis

A new trend emerged toward using misleading political analysis as linguistic mask for hatred.

Opinions appear rational but are charged with discriminatory language excluding a specific category or party.

Often concluded with phrases suggesting objectivity like “we speak the truth even against ourselves,” while hiding behind them systematic hostility framing.

This strategy makes discourse more dangerous because it gives it false intellectual legitimacy.

6. Stability of Hostility Symbols and Transformation of Its Tools

Despite changing methods and media, symbols and targets of hatred remained largely stable.

The same political opponents and regional parties that were targets in 2023 still remain the focus of hostile discourse at the end of 2025.

But tools changed: from articles and long posts to short clips and condensed slogans.

This stability in “hostility logic” versus evolution of its tools indicates entrenchment of hatred structure in collective consciousness.

7. Victim and Perpetrator Duality

In some posts, a tone of regret or justification appeared, where the user speaks as a victim of circumstances or “in response to previous hatred.”

This pattern shows that hostile discourse has acquired confused self-awareness; it justifies violence as self-defense, not aggression.

Thus, hatred becomes a closed loop: each party sees itself as victim, so produces new hostility to justify its past.

8. Growing Regional Discourse as Cultural Identity

Notable increase was observed in using geographical or tribal affiliation as a tool for building digital identity.

Digital pages and personalities began defining themselves by region or tribe before any intellectual or political affiliation.

This trend re-entrenches social division as “natural difference,” making it more dangerous because it gives cultural legitimacy to discrimination.

Conclusion

Results can be summarized that Sudanese hate speech is no longer merely linguistic interaction but an integrated communication structure combining past and present, emotion and symbol, laughter and violence.

Hatred today hides behind sarcasm and analysis, promoted through algorithms rewarding repetition, making it more flexible and widespread than ever.

The most dangerous aspect of digital hatred is not its presence but its ability to survive. It does not disappear with the event’s passing but reshapes itself in each time with new language and familiar face.

Special Focus

“How Do Platforms Create Hatred Memory?”

Hate speech in Sudanese digital space is no longer merely a product of enthusiastic users or conflicting groups; it has become part of an integrated algorithmic system ensuring its survival and intensifying its spread. Platforms are no longer neutral as they were presented, but have evolved to become active factors in building digital memory of hatred, through their technical mechanisms that recycle hostile content and amplify it almost automatically.

First: Algorithms as Active Memory

Comparative monitoring shows that the three platforms (TikTok – Facebook – X) share one characteristic:

The more engagement with hostile content increases, the more its presence on the display interface increases.

- On TikTok, the “For You” algorithm works to push emotionally stimulating clips — regardless of their nature — to a wider audience, transforming hostile content into a profitable interactive product.

- On Facebook, the “similar pages suggestion” system leads to hostile discourse recycling through intersecting networks, transforming the post into a series of continuous recalls.

- As for X, it revives old tweets through “retweet with comment” feature, to appear as new discussion, while actually being a rebroadcast of old memory.

These technical mechanisms make platforms not only a space for spread but a mechanism for preserving and retrieving hate speech — like algorithmic collective memory that forgets nothing.

Second: Attention Economy and Hostile Content Intensification

In the platforms world, attention is the most important currency.

And everything stimulating anger or polarization generates engagement, thus profits.

- Data showed that hostile clips on TikTok achieve viewing rates three times higher than regular content.

- In contrast, content calling for coexistence or dialogue is often marginalized or not recommended by the display algorithm.

In this sense, platforms contribute without announcing to transforming hatred into an economic resource, ensuring engagement continuity and time users spend in front of the screen.

Third: Selective Memory – When Truth Is Forgotten and Anger Recalled

One of the most dangerous platform characteristics is their ability to recall anger and ignore context.

When republishing an old clip, the platform does not indicate its original date or background.

Thus, users interact with it as if it were a new event, leading to reproducing old feelings without review or awareness.

Thus platforms transform into selective memory that does not remember facts but preserves feelings of anger and polarization and re-pumps them whenever they fade.

Fourth: From Content Management to Behavior Shaping

The deeper result is that platforms no longer merely transmit hostile discourse but shape the way of thinking and interacting with it.

They teach users that anger-provoking content “is rewarded with reach.”

And create an environment where groups reproduce themselves within closed “identity bubbles.”

Also reshape users’ linguistic behavior, so they adapt to engagement algorithm instead of rational dialogue standards.

Thus hatred transforms from discourse to sustainable interactive behavior, nurtured and implicitly rewarded by the platform.

Fifth: Toward New Awareness of Algorithmic Environment

This analysis emphasizes that addressing hate speech is no longer only individuals’ or states’ responsibility, but has become linked to reforming the technical structure itself.

Platforms must bear part of ethical responsibility in indicating old re-circulated content.

And activate tools warning of “materials that incite violence or division.”

Also support digital media education initiatives that teach users how to read time and context in published content.

Conclusion

Digital platforms, with their complex mechanisms and non-transparent algorithms, have become like a hidden writer of digital history of hatred.

They preserve what is said, recycle it, amplify it, until it becomes part of collective consciousness.

Therefore, confronting digital hatred cannot be done without understanding how platforms work to produce and sustain it. The war on hate speech is not only a battle against words but against the machine that repeats and revives them every day.

Case Study

“Three Platforms… Three Languages of Hatred”

This axis presents three case studies selected from the sample monitored in November, to clarify how Sudanese hate speech renews over time and platforms.

These cases reveal that hatred is not one type of discourse but a network of methods and symbols taking different appearance in each digital environment.

First: TikTok – “Comedy That Hides Hostility”

Case Description: Among 14 TikTok accounts, a group of clips emerged using sarcastic performance and popular humor as cover for regional and ethnic discrimination.

One monitored clip (originally published mid-2024 and re-circulated in November 2025) shows a person performing sarcastic dance to traditional music tunes, while words are accompanied by sarcastic references to a certain group’s dialect and physical features.

Qualitative Analysis:

- Despite the comic form of content, the implicit message carries clear ethnic discrimination.

- The clip achieved more than 120,000 views during the monitoring period, most resulting from repeats and sarcastic comments.

- This pattern reflects hatred’s transition from explicit discourse to disguised incitement with humor.

- TikTok here shows how the platform can transform symbolic violence into widely spread entertainment product.

Conclusion: TikTok represents a space where entertainment and incitement coexist in one format, making hatred more acceptable and harder to control.

“One laugh may hide a whole discourse of discrimination.”

Second: Facebook – “Open Regional Memory”

Case Description: Among eight Facebook accounts, a public page was observed republishing clips and images from 2023 about conflict areas in Darfur and Kordofan, with new comments linking them to December 2025 events.

Users interacted with these posts as if they were new documentation, despite being more than a year and a half old.

Qualitative Analysis:

- The case shows how the platform contributes to mixing times: past appears present, and archived content is used as mobilization tool.

- 65% of monitored comments carried inciting or violence-justifying phrases, confirming that absence of indication to original time reproduces anger and hostility.

- Also, collective sharing and repeated republishing created a new “digital memory chain” redefining reality according to regional narratives.

Conclusion: Facebook works as a repository for collective memory, where the past is reshaped to serve current conflict.

“What is republished is not read as history… but as an unfinished event.”

Third: X (formerly Twitter) – “Analysis Masked as Incitement”

Case Description: In X account sample, a series of tweets reactivated from mid-2023 was monitored, describing a political group as “the reason for state collapse,” with links to old clips re-circulated after a political announcement in November 2025.

Although tweets were published in a different context, they were republished as if a direct response to the current event.

Qualitative Analysis:

- Discourse in this case takes the form of rational political analysis, but employs accusatory and generalizing language.

- 70% of engagement came from anonymous accounts, republishing tweets without verification.

- This pattern reflects what is known as “analytical inciting framing”: meaning using opinion and criticism language to justify hatred.

- Also shows how “political analysis” on the platform transformed into a soft tool for symbolic violence.

Conclusion: X represents the space where linguistically justified hatred is formulated — meaning that presented in the form of “legitimate opinion” but reproduces exclusion.

“Not all angry words are explicit… some analyze.”

Case Studies Summary

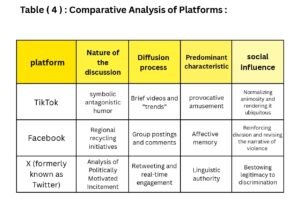

Comparison between the three platforms reveals three integrated patterns:

Table No. (4)

These cases indicate that Sudanese hatred is no longer produced in its moment but managed through a temporal system where the three platforms integrate to formulate extended digital memory — memory that speaks three languages and feeds division in three ways.

Recommendations:

“From Monitoring to Response: Toward a Responsible Digital Environment”

Monitoring and analysis results during November and December highlight that hate speech on Sudanese digital platforms is no longer merely a linguistic phenomenon but an intertwined interactive system feeding on algorithms, collective memory, and weak media verification.

Therefore, dealing with it requires multi-level response including technical, legal, and awareness.

Following are the most prominent recommendations extracted from this edition’s results:

First: On Social Media Platforms

- Including clear temporal indicators on republished or circulated content, to avoid temporal misleading that reproduces old hatred in new contexts.

- Modifying recommendation algorithms to reduce reinforcing hostile content even if highly engaged, giving priority to content supporting coexistence and dialogue.

- Enhancing local reporting mechanisms through regional offices understanding Sudanese context, instead of relying on general standards ignoring linguistic and cultural sensitivity.

- Obligating influential content creators to include clear warnings or contextual clarifications when republishing materials from previous periods.

- Activating partnerships with civil society organizations to help identify inciting discourse in local language and precise social contexts.

Second: On Legal Authorities and Policy Makers

- Developing digital legislative frameworks dealing with hate speech as a continuous communicative crime, taking into account republishing and circulation as harmful practices no less than first publication.

- Updating media laws to include short broadcast platforms like TikTok within censorship and accountability scope, similar to Facebook and X.

- Creating a specialized digital crimes unit concerned with monitoring and documenting inciting content judicially to ensure accountability.

- Enhancing regional judicial cooperation with neighboring countries and international justice organizations in tracking cross-border accounts promoting hostility discourse or violence incitement.

Third: On Civil Society Organizations and Media

- Launching counter-digital campaigns redefining concepts of belonging and identity positively, using communication media language itself to confront hatred with humanitarian and creative content.

- Training journalists and creators to monitor linguistic and semiotic indicators of hate speech, to avoid inadvertently reproducing it.

- Supporting “alternative digital memory” initiatives documenting coexistence narratives and civil resistance, to be a counterpart to hatred memory prevailing on platforms.

- Enhancing digital media education in schools and universities, enabling youth to read time and context in content they consume or republish.

Fourth: At International and Regional Level

- Urging platform-owning companies to commit to human rights charters in content management, especially in fragile environments and internal conflicts.

- Allocating technical and financial support to independent local monitoring initiatives, as they provide qualitative understanding that global artificial intelligence tools cannot achieve.

- Integrating digital hate speech in international fact-finding mechanisms as one of the basic drivers of mass violence and subsequent violations.

Fifth: Strategic Proposal for Next Publication

“Accounts Under the Microscope” team proposes that the January edition address a special focus titled:

“Artificial Intelligence and Programmed Hatred: From Interaction to Guidance”

To highlight how artificial intelligence tools can become part of the problem or solution simultaneously, especially with entering the “automated influencers” (AI influencers) stage.

Conclusion

Curbing digital hatred is not achieved only by deletion or censorship but by re-engineering the communication system itself to become more aware of time, context, and ethical responsibility.

The battle is not between “discourse and responding to it” but between memory that reproduces hatred and awareness that rereads it.

Conclusion

“When Memory Speaks… Time Silences”

This edition of “Accounts Under the Microscope” reveals that hate speech in Sudanese space is no longer a passing event or immediate reaction but has transformed into a living communicative structure extending in time, renewing itself through each platform, each algorithm, and each republication.

Temporal and comparative analysis clarified that digital hatred is not only what is said today but what is retrieved from yesterday to be reinterpreted in the present — in a continuous cycle of anger, memory, and misleading.

Monitoring showed that platforms are not merely discussion arenas but meaning production spaces, where belonging, identity, and violence are simultaneously reshaped.

Therefore, confronting hatred cannot be reduced to monitoring or deletion but requires critical awareness of the algorithm itself and the memory governing our presence in digital public space.

In December, it became clear that language is no longer only a means of expression but has become a tool for repetition, survival, and staying — even for hatred itself.

It adapts, laughs, dissolves then returns in new form, because it lives in a space that knows no end: the platforms space.

But amid this noise, hope remains:

Just as hatred reproduces itself, awareness can also be reproduced, building new discourse transcending division and restoring humanity of communication in a turbulent digital time.

“Hatred feeds on repetition, but awareness feeds on understanding.”

And from here begins the next monitoring mission — not to monitor hatred only, but to draw new maps for digital coexistence in Sudan and beyond.